I was first introduced to Simplicissimus Magazine through Jack Potter, a teacher of mine at the School of Visual Arts. Jack owned copies of the magazine that he put in portfolio binders, a practice which inspired me to do the same and is something that I’ve talked about in previous articles. One day, during a class break, he whispered “Daniel come over here” and, to my surprise, he brought one of his Simplicissimus collections to look at. After a few minutes passed I heard “Hey can you flip back to that one?” and “Oh wow look at that!”. I then noticed that I was now surrounded by a majority of my fellow classmates. The reaction that day pleasantly surprised me because it’s one of my favorite publications and one that I think deserves greater attention.

Since that time I now own three library collections of Simplicissimus from the years 1905, 1906, 1908 and 1911. The collection from 1908 had no cover and was falling apart, so I put it in a portfolio to keep in good condition. The one from 1905-1906 is taped together because the binding is weak. Keep in mind that these are over 100 years old!

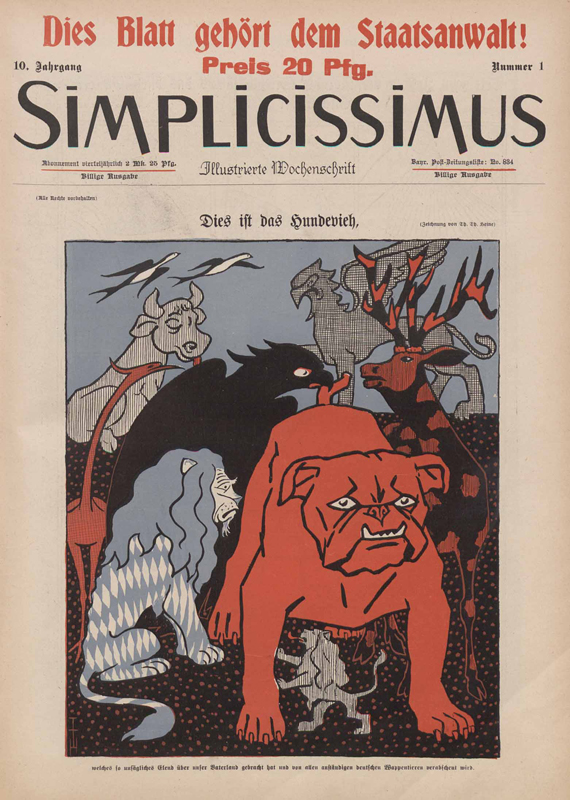

Also of note you’ll notice an image of a red bulldog on one of the covers and in the illustration that I shared to begin this article. That piece is by an artist named Thomas Theodor Heine and was the mascot for the magazine. The bulldog symbolized the Volk, or common people. As you can see the dog broke free of its chain.

Simplicissimus was a weekly publication from Germany that was founded by Albert Langen and ran from April 1896 to 1967, with a hiatus in 1944-1954. Langen’s inspiration for the magazine were the satirical publications that he saw during the late 1800’s such as Punch, Le Rire, and L’Assiette au Beurre.

For the first issue they printed 480,000 copies, not because they were optimistic but because they wanted them for publicity reasons. That issue sold 10,000 copies. As the magazine continued, its circulation grew and in 1904 it reached at least 65,000 copies (some say 85,000). Each issue of the magazine is 10 5/8” by 14 7/8” with art on almost every page (minus the ads). One thing I like most about Simplicissimus is how well it showcased the illustrations (there’s always a few full pages). It was also reproduced using an advanced and expensive zinc-etching process.

Due to its subject matter the magazine was officially viewed as immoral, revolutionary and socialistic. In 1898 Langen published an issue that outspokenly jeered at the Kaiser’s pan-Islamic diplomacy in the Palestine region. As a result, two contributors to the magazine, T.T. Heine and Frank Wedekind, were jailed for six months and Langen had to escape Germany. He returned in 1903 but only upon payment of a heavy fine. Simplicissimus never again attacked the monarch so directly, but continued to lampoon objectionable government policies, the German bureaucracy, the military, religion, the smug bourgeois and many other issues of society.

Here are three war cartoons by Wilhelm Schulz.

In 1906 Thomas Theodor Heine led a group of staff artists and writers in a successful demand for profit-sharing and a greater say in the direction of the magazine. Up until that point Langen owned everything and even claimed copyright of the original drawings reproduced in its pages and offered them for sale to the public, with a percentage going to the artist. Now the artists retained ownership of their own artworks.

In 1908 and 1909 two of the magazines chief artists died, Ferdinand von Reznicek and Rudolf Wilke; so did its founder-publisher Albert Langen. Fortunately, the rest of the staff was already accustomed to decision-making and carried on without any major problems until the outbreak of the First World War. The staff felt that Germany was in the right and some wished to cease publication, since they felt that the nation should not be ridiculed during wartime. Another group, led by Heine, convinced them to continue publication, but as a patriotic publication. This, in turn, caused the magazine to dull its satirical tone.

After the war the circulation for Simplicissimus dropped to 30,000 and never again attained a consistent political view. It still attacked statesmen of all fractions and considered the radicals of the right, such as Hitler, to be enemies that were as dangerous as the left-wing Communists and Spartacists*. Then in 1933 Heine fled to live another fifteen years in exile. The artists who remained had to conform to new standards and Simplicissimus lost much of its edge. It continued publication until the final issue in September 13th, 1944.

A new Simplicissimus was published in 1954, but was not distinct enough to stand out and went under in 1967.

Throughout it’s history Simplicissimus published the work of notable artists such as: Eduard Thony, Henrich Kley, Jules Pascin, Bruno Paul, Ragnavald Blix, Karl Arnold, George Grosz, Rudolf Wilke Thomas Theodor Heine, Kathe Kollwitz, Olaf Gulbransson, Wilhelm Schulz, and many others.

Let’s take a look at four artists from Simplicissimus and end with a miscellaneous selection of illustrations. The images all come from my library collections.

Heinrich Kley is known for his loose pen and ink drawings of animals and women. You’ll see his illustrations throughout Simplicissimus, but rarely any bigger than a spot or ¼ page size. Kley’s artwork was later used as inspiration for the Disney animated films Fantasia and Dumbo. What I like about his art is how loose and lively it is. Nothing is static (which I’m sure is one reason why Walt Disney was drawn to it. No pun intended).

Here’s a selection of his illustrations from the magazine.

In these two pages you’ll see a rare full color sequence.

Another artist, and one who worked for the magazine for decades, is Eduard Thony. He’s someone that I’ll go into more depth in a future column, so for now just I’ll share a few images below. I love the ‘character’ that he captures in his figures along with his use of big bold shapes!

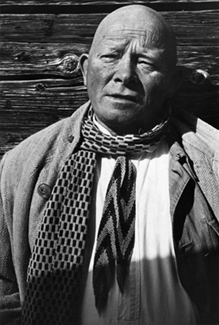

Next up is an artist named Olaf Gulbransson, a Norwegian artist who moved to Germany in 1902. His illustrations for the magazine are typically drawn using a clean ink line with an exaggeration of the figures. He also did many pieces that were a sequence created in panels, which for it’s time must’ve been the early days of comic strips. Outside of his work for Simplicissimus he did illustrations for books, set and stage designs and was a professor at the academy of art in Munich.

He even looks like one of the figures you might see in a Simplicissimus illustration!

Here are a few samples of his illustrations.

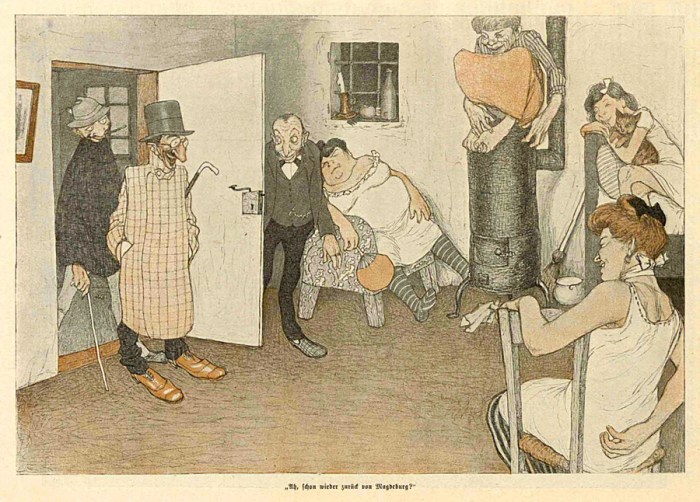

Jules Pascin first worked for Simplicissimus when he was still a teenager and got the job through a recommendation of a writer named Gustav Meyrink. His father objected to the drawings that he did for the magazine so Jules adopted the pseudonym of Pascin (an anagram of his real last name Pincas). Jules later become known for his drawings and paintings of Parisian prostitutes and for his bohemian existence in the Paris of the Twenties.

The figures in his illustrations feel a little odd and twisted, as if something is a bit ‘off’ in the world he created. An example below is the image of two men entering a room. They look happy, but one woman is sleeping, another person is sitting on top of a heater and I can’t tell if the people are happy to see the them or if something else is going on. It’s a strange scene that I can’t quite figure out. Perhaps if I could read the German caption that would give me some insight into the image?

Stanley Appelbaum in his book about the magazine said that Simplicissimus is “one of the greatest picture magazines in the history of journalism”. I agree with him, but as I’m sure you can tell I’m also biased. I love that it’s a magazine that was critical of society and had a rebellious spirit (for a period of time). On top of that it was controlled by the contributing artists, which is something that rarely happens in any commercial outlet.

If you enjoyed the illustrations that I shared in today’s article, please tune in for the next few months as I dig a little deeper and focus on three of my favorite artists who worked for the magazine.

Below is a gallery of illustrations from Simplicissimus by various artists.

*The Spartacist uprising was a general strike in Berlin from January 5th-12th, 1919.

Stanley Appelbaum’s book is titled “Simplicissimus: 180 Satirical Drawings” and was published by Dover.

Excellent research!!!!!

Simplicissimus is amazing, I love it too. So modern and bold in its graphic aproximattion to illustration. Compositions, colors and concepts. Incredeble. Even today vanguardist. Thank you so much for your article and your passion.

Hey, do you know how can I reach an english version of the magazines? Much appreciated

thanks for these fabulous illustrations! Do you have issues of the year 1906 or earlier? I am studying on an etching by Walter Sickert, and the etching is probably from an illustration in the Simplicissimus!

Thank you Daniel for all the brilliant work covering Simplicissimus – and in particular the piece on Eduard Thony – I have poured over it all :) Please could you kindly answer a question – I LOVE one of the illustrations here on the right hand page of the image called ‘Simp5’… please could you kindly tell me the artist name? – and any other details like the publication if possible – I’d love to track it down and find out more… MANY THANKS IN ADVANCE – Ben

Ben, that’s an illustration by Bruno Paul. I’m not sure the exact issue it appeared in.