by Mark Stutzman

A global pandemic abruptly altered the interpersonal relationships that exemplify the creative team experience. But these people who live on the edge of convention are pliable and technologically skilled, allowing them to migrate their work disciplines into their homes. Suddenly, the entire creative industry, like many others, is living the lifestyle of a freelancer, tethered together only by WIFI and self-governance.

Illustrators and art buyers share this independent commonality unlike ever before. Since the golden age of illustration in the 1930s, the dynamic between maker and buyer has been distinguishable and separate. An artist’s life was in stark contrast to the office-dwelling cohort who paved the way for the anticipated art. Outside talent would occasionally visit the workplace to share a portfolio and make an impression to snag a new assignment.

Whichever way one sells a product or service, illustration emerges from a joint interest in making something new and unique. The one-on-one between art directors, art buyers, clients, editors, producers, film directors, and ideally, the artist remains a constant place for synergism. This treasured collaboration is fertile ground for inventing and reflecting memorable images of who we are. Our cultural, societal narratives and aesthetics make for great illustrations.

Besides the fading in-person interview, art directors once relied on their Rolodex (today’s contacts), artists’ directories, and direct-mail promotional pieces to keep up with the trends and emerging talent. Portfolio review days (speed-dating for creatives) were a popular way to streamline the search for new talent and seek bonds with creatives outside the office walls. It has always been competitive and cultivating the up and coming or employing seasoned veterans was a path to earning art directors and designers’ prestigious awards and recognition.

Finding that talent can be daunting and ongoing, according to Eng-San Kho, one of the partners at Love & War, a small but chic Manhattan branding agency. He remembers a time when his office was inundated with sales sheets and promotional postcards from artists and photographers that fell into three categories. Some samples were discarded, some saved for later, and a few pinned to the walls. Today, online search engines make finding talent a bit easier for art directors like Kho, but the task of sifting through so many options and search criteria can still be all-consuming.

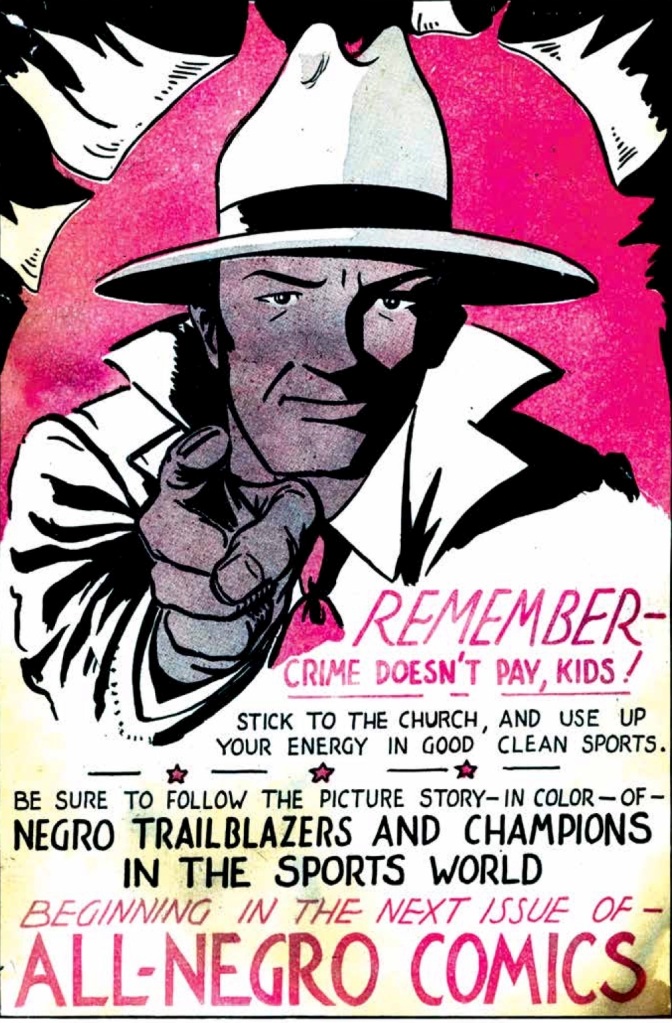

Image Above: Created by Mark Stutzman. Tear-out poster in Billboard Magazine for Art Director Eng-San Kho and the team at Love & War for EMI Music Publishing.

As art directors and buyers cull the internet for viable talent, stock catalogs and in-house images gnaw away at commissioned work.

“If we’re up against a tight deadline we often rely on stock photography,” Kho explains. “The cost of licensing existing art versus commissioning new art is often easier.”

The artist’s hand can be substituted with cobbled-together imagery and digital tricks of the trade. Although it can be good-looking, an assemblage pales next to the magic that emerges from collaborating minds. One may fill the space nonetheless, and without the need for commissioning outside services or expanding creative margins.

Kho explains some clients may not be able to handle the creative process that comes with commissioning work. It can impose a greater demand than they can professionally manage. However, someone on staff who is familiar with developing original concepts for illustration can coach coworkers and clients to make it an enjoyable and exciting endeavor.

The digital age is now on simmer and a staple of everyday life, crossing every demographic. Standing out is increasingly difficult when every designer has access to similar tools and stock imagery. A visual sameness can be safely on-trend but misses the individuality of fabricating art out of thin air.

Interestingly enough, a dearth of originality is carving out a place for illustration. Some firms are engaged in reviving the tradition of print media and product premiums, to reach audiences with a tactile advantage – something their competitors may not be able to afford. There is greater awareness and appreciation for traditional visual media, and hand-crafted art amidst the digital glut of Creative Cloud effects aimed to resemble illustration.

Technology connects everyone but the convenience of clicking can also build a virtual wall with single-dimension communication. Working on a project from start to finish is possible without ever speaking in person – but that does not mean anyone should fall prey. Each project is an opportunity to foster camaraderie, trust, and inspiration between creative services, and the final product benefits from those human tenets.

Greg Burke, Senior Creative Director at Atlantic Records, is always searching to see what visual talent is available to him – not a one-size-fits-all proposition. He is tasked with the complex role of developing visual continuity for top recording artists on multiple levels. Developing imagery, packaging, and merchandise is a labyrinth riddled with subtlety. The nuance, uniqueness, and essence of each recording artist’s sound must translate into thoughtful imagery that represents them.

For many years, Burke has bookmarked his favorite artists in hopes that one day, the right project will ignite a fresh working relationship. He sometimes seeks creative talent that fits a specific assignment. New searches, with a specific creative direction in mind, keep him adding to his collection of illustrator’s names. Burke’s years of experience have taught him that some illustrators’ styles may change over time. Old reference he fondly recalls that fits an immediate project may no longer be part of their repertoire. Although for him, keeping his reference arsenal handy still helps spark ideas.

Burke’s search criteria begins by finding talented individuals. He then looks at the body of work an artist has curated to ensure that a single image catching his eye is not a fluke but consistent with the larger body of work.

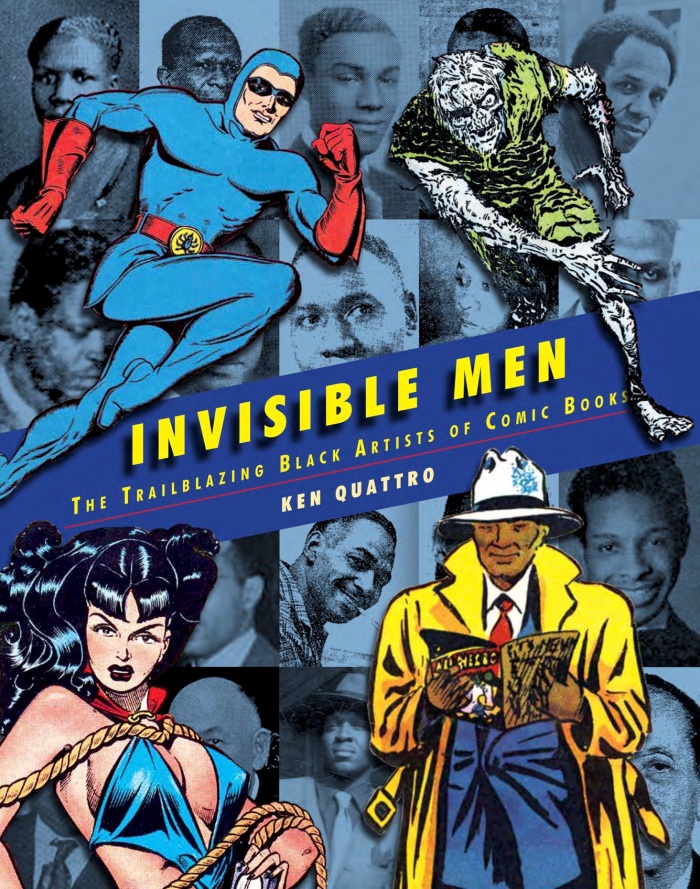

Image Above: Created by Mark Stutzman for Art Director, Greg Burke. Cee Lo Green’s Lady Killer Album under the Atlantic Records label. Cover design used for promotional merchandise instead.

“There are times when you may see an image that you love but the rest of the portfolio is inconsistent and all over the place,” says Burke.

He is reassured if each portfolio piece is as strong as the one that reeled him in. He is also okay with artists having diverse styles as long as they show mastery in each. When shopping for an artist, Burke looks at the collective strength of an artist’s work to show him they can habitually fulfill a creative direction.

As a courtesy to the talent and to preserve the integrity of a project, Burke says he will never ask an artist to create something he is not confident is within the scope of what that artist can do. In his opinion, that is a setup for failure.

With the reality of hard deadlines, Burke requires professionalism from every artist. Knowing that each person works differently, he will engage in a direct conversation about timing and process. As a good gauge, Burke will select a piece an artist has completed and ask how long it took from start to finish. A project schedule can then be built from that example.

Spicing things up.

Kho and his team are passionate about infusing art into their agency work whenever they can.

“We try out a specific artist who might not be the obvious choice for a project,” he says. “We like to see what they’ll bring to the table.”

More often, Love & War fits the assignment to the artist in the same way they fit their work to their client’s needs. Ultimately, it is about making sure the work serves the targeted audience and meets the business goals rather than being dictated by a design agenda or trend, according to Kho.

Artist relationships are very important to Kho and his team who take advantage of video calls whenever they can. Being able to see who their speaking with personalizes and expedites much of the working process. Kho also likes that the work takes center stage with the screen-share option on video calls with clients. Without the distractions of others in the room, all the attention is on the presentation.

Their team like having creative people they can rely on or have in the cue for future work as well. Returning to an established, good working relationship adds a level of confidence and efficiency that Kho says can help a project run more smoothly overall.

When eyes meet.

Burke describes the personal relationship a bit differently, depending on the circumstances.

“There are illustrators who will always be a go-to because of the quality of their work and the great communication skills,” Burke says. “But there are times that a project will be a one-off, and you are fully aware that you may not be using this illustrator again.”

Creative briefs can also dictate how much Burke needs to steer a project. Sometimes he requires control of the final product, whereas others have a bit more flexibility and more input from the artist themselves. Art directors like Burke want artists he works with to understand the parameters of commercial art, however. Commercial art sometimes comes with the disappointment of client input, so it is essential to Burke that artists understand the confines of the trade.

There is a distinct difference between commercial and fine art. Art directors appreciate illustrators who embrace the commercial world and how sometimes you have to take one for the team rather than indulge individual expression.

“An illustrator must also understand that at times directions for revision will come from a recording artist or other outside sources,” says Burke.

He realizes that any necessary revisions to appease the client may not enhance the artwork. In those moments, both he and the illustrator share in the disappointment. Bonds can form throughout the journey of pleasing clients, even if the outcome strays from the original inspiration.

How this valued relationship begins between the illustrator and the commissioning body can vary. It may result from a deliberate search using directories like the Workbook or through referrals from colleagues. Love & War also relies on word-of-mouth referrals for new business, talent connections, and everything in between.

“We don’t seek referrals for new commissions, but we do our best to spend enough time interviewing new-found illustrators to make sure we’re all aligned on scope and expectations,” says Kho.

There may be some internal conflicts about sharing talent you discover as an art director, according to Burke. On one hand, if he finds an illustrator he loves, Burke wants some exclusivity with that illustrator, but on the other hand, he does not want to see that illustrator to miss out on other opportunities.

“I freely share illustrators whom I respect and who’s work I admire with colleagues,” Burke says proudly. “I’m a little jealous when someone else gets to use one of my recommendations that I may never get to use myself, but I get over that pretty quickly when I see the amazing work in the end.”

Burke also reserves his artist recommendations for art directors he respects. His experience in matchmaking is the product of his interest in facilitating impressive visual work.

Ultimately, relationship-building is an essential part of sustaining a career as an illustrator. Work is not as plentiful as it once was, so solidifying connections can keep the door open for future assignments. If each new relationship only results in one project, maintaining a full schedule will require an exhaustive roster of new clients. And as Kho explains, assignment work is not part of every incoming project. Much of what they do is design solutions and does not require illustrative works at all.

For an illustrator, building valued and sustainable relationships boils down to a few core elements – making deadlines, high-quality and consistent work, good communication, and accommodating a client’s needs. A successful commission is measured by delivering what has been promised to the client.

Making commercial art for a living will always have its challenges and forever be changing. If the unchangeable aspect is what propels the kinship between artist and buyer, there is a bright future toward which the two entities can look forward.

Article Author, Mark Stutzman is Best known for his rendition of the young Elvis Presley Stamp, Stutzman’s illustrations are used in advertising, on products, posters, magazines, book covers, and other niche markets. His work is well-known in the entertainment business; on Broadway: Young Frankenstein, The Musical, Annie Get Your Gun and in the mystical realm of David Blaine and his event “art” posters. He has created artwork for movie products and premiums for Batman, Jurassic Park, and Space Jam, as well as book covers for Steven King and is an acclaimed playing card artist. With a client list topped by McDonald’s, DC Comics, MAD magazine, The New Yorker, Nickelodeon, Rolling Stone, Microsoft, Time, and Esquire, he’s had the opportunity to influence many worlds through his illustrative works.